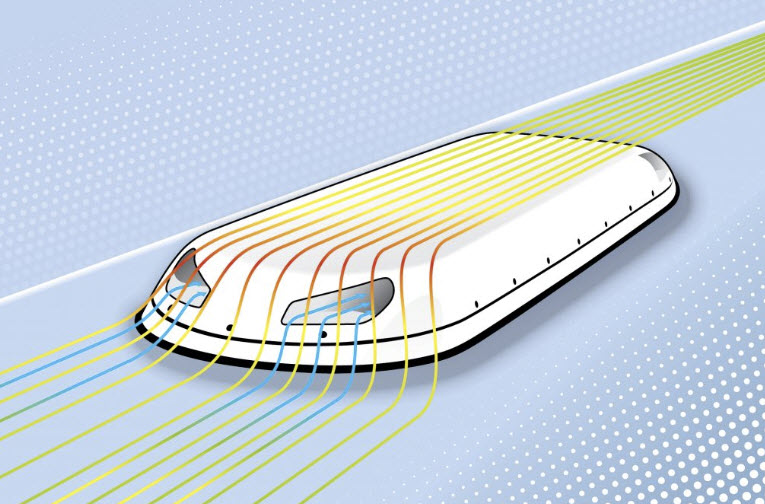

High and low pressure zones drive flow through interior cooling channels. Image: Marcelo Cáceres | APEX

Written for APEX Experience Magazine – Issue 9.5 – December 2019/January 2020

The absence of moving parts means electronically steered antennas are reliable and easy to install, but they have a downside that Carlisle Interconnect Technologies says it can solve.

Heat is the enemy of electronics. The more powerful the processor or component, the more heat is generated. That’s why your laptop likely has a fan, and why massive server farms such as Amazon Web Services or Google need colossal amounts of cooling to keep servers from overheating and shutting down.

It’s no different when it comes to airborne Internet connectivity. The antenna system needs to be continuously operating – generating heat – for passengers to stay connected. It might seem simple to keep an antenna that’s mounted on the outside of an aircraft’s fuselage, above the cabin, nice and cool. Why not just cut a hole in the cover and let the airflow do the rest?

Not surprisingly, it isn’t that simple. The heat of the sun on the radome adds to the thermal load, as does aerodynamic heating, whereby the passing of air at high speeds (in the case of commercial aircraft, 575 miles per hour) is converted to heat. The path for cooling airflow must be free of dirt, ice and moisture, and the outside skin of the fuselage can’t be used to dissipate the heat. And it’s getting more complicated as new power-hungry phased-array, flat-panel antennas begin to appear. Compared to current mechanical, motor-steered dishes, a flat-panel antenna is steered electronically, with different elements of the array receiving and transmitting beams.

While mechanically steered systems might consume a couple of hundred watts of power, electronically steered antennas (ESAs) can use as much as 2,000 watts. Think of a high-powered hair dryer in the antenna enclosure, and it’s clear that there could be a problem with heat.

Carlisle Interconnect Technologies (Carlisle IT) is working on a solution. Recognizing the opportunity for compact ARINC 781 form-factor ESA installations on regional passenger airliners and corporate aircraft, the company has created an integrated cooling design that is now moving from simulation to a hardware testing phase.

“The patent-pending part is an isothermal transfer plate that is integrated with the adapter plate to help dissipate heat away from the [antenna] arrays,” said Kris Samuelson, director of sales, IFEC and Interiors, Carlisle IT. “Along the length of the adapter plate you have a heat-pipe-like system … what we call integrated duct radiator channels. They act like vents, helping to dissipate the heat out the aft end.”

Carlisle IT takes advantage of the low height of an ESA, with the complete installation only about three inches above the fuselage, compared to around 13 inches for a mechanically steered system. According to Samuelson, the new scalable solution will support a wide range of aircraft and hardware systems.